A Fresh Start

After taking a good, hard look at the work I’d done previously, I felt that the game was becoming bloated and simply not fun. I decided it would be the perfect time to try something new, so I started drawing up a simplified/modified version of the original.

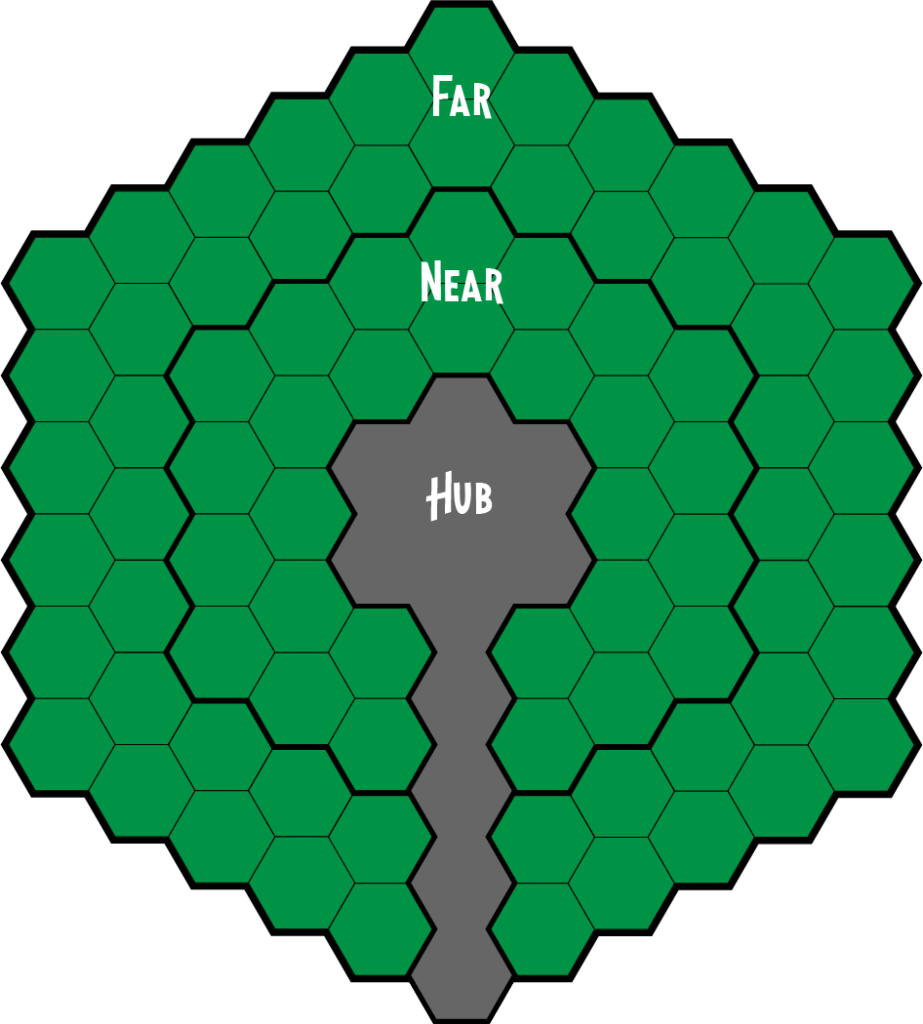

Rather than having players each play as individual lands, each player would take on the role of a designer. Each can build anywhere in the park, which removes some of the issues of competing against opponents that you can’t affect. In the previous iteration, you can only affect your neighbors to the right and left of you, but in this version, there’s greater potential for each person to affect the other players.

I’m still working to put these ideas together into a full game, but the base seems much more solid to me now. There are also several systems that I’d like to work with.

Systems

Attraction Interactions

I still love the idea that attractions interact with the world around them – for example, placing a gift shop next to a ride gives that gift shop a boost to money earned. More people would travel through it, so it makes sense that the gift shop would make more money in that case.

Research

I’ve always loved skill trees in board and video games. I figured it could be really interesting to see how that would translate into a game like this. The idea would be that players start with the bottom-most blueprints at the start of the game (Flat Ride, Street Performer, and Snack Stand). As they play, they can upgrade those by following the paths upwards. Some rides, like a Simulator, require that both Thrill Rides and 4D Movies have already been researched.

The Themed Lands

Primedievaland is based in a medieval city filled with a wide assortment of dinosaurs. A wizard’s backfiring spell brought the creatures to the land, but the townspeople learned to live side-by-side with them. Here you’ll find knights competing in raptor-back jousting or eat mammoth mutton.

The Woodworks is the site of a former industrial complex. Though the air was once filled with the sounds of machinery and labor, things grew quiet after the area was abandoned. Plants have recently overtaken the machinery, and things have started moving once again.

A city made entirely of ice? They said it couldn’t be done, but here we are. Millions of visitors crowd the streets of the big city, amazed by the artistic stylings of the architecture. Here, you can catch a show on Brrrrroadway or pick up some gifts at Merch of the Penguins.

The Shining Shoals Boardwalk was once a bright, popular spot for families to visit. That is, of course, until the incident… The numerous ghost pirate and kraken attacks since then have left the boardwalk in shambles. Some, though, are interested in bringing the area back to life as an tourist spot. Good luck with that.

Theming

Very few board games have no theme. Even classics like Chess feature pieces thematically appropriate for its war strategy simulation. Especially when looking at modern board games, you’re hard-pressed to find games don’t revolve around a specific setting, story, or theme. The question then becomes this – how far should you take the theming? How much should you draw from the theme for your game? In designing Theme Sparks, I wanted the game to be thematic with many mechanics and ideas tied directly back to theme parks. Theming comes with several benefits – for one, if you’re running low on ideas for mechanics or settings, you can take a look at the inspiration and use ideas pulled from it.

Several of my ideas for the game came directly from its theme park inspiration. For example, a lot of thought goes into the placement of attractions in parks. You’ll usually find a large set piece or attraction towards the back of a park. This is called a park’s “weenie” (a term coined by Walt Disney referring to leading a horse with a hot dog weenie on a stick) and is used to draw guests to certain areas. That led to the idea of InterAttractions (attraction interactions?), which give extra bonuses to attractions based on their placement. Placing big attractions in the back of a park give bonuses to the number of visitors, just like putting a gift shop next to an attraction boosts money spent.

Game vs. Simulation

Another big decision in game design is choosing to make a game or make a simulation. The important difference between the two lies in the details of the experience. If you want to make a simulation, the mechanics, setting, and gameplay should be as close to the “real thing” as possible. A simulation is meant to do exact what the name implies – simulate the real thing without holding back on minute details. A game, on the other hand, has an experience tuned to a desired feeling (fun, stress, fear, etc). It’s okay if the details of the experience don’t match the real thing, as long as the right feelings are achieved.

My goal with Theme Sparks was to go for the “game” experience rather than simulation. I didn’t want to give guests the experience of tracking the effect of marketing campaigns on ticket sales, creating detailed Gantt charts of maintenance for rides, and negotiating IP merchandising. I want people to have the experience of what they think theme park designers do – building shows and rides, mapping paths through the park, and ensuring their guests are happy and having fun. That may not be how the real world works, but it captures the right feelings.